Saturday, May 14, 2005

Intelligent Design vs. intelligent design

First, a little history about my last post. Before I wrote

it, I had read some articles pointed out by thx on his post here.

It's a set of four articles about the relationship between Christianity

and psychotherapy. Although I disagree with a lot of what the

authors have to say, I enjoyed reading them, and found them to be both

thoughtful and helpful.

One of the things about humans that I think is among the most interesting, is the fact that two intelligent, sincere, well-meaning people can live in the same Universe, have access to nearly the same facts, and yet hold diametrically opposed opinions. I have known for some time that there is a certain tension between Christianity and psychotherapy, but it always has perplexed me. Most of the therapists I know are observant of some organized religion; most of those who are not, consider themselves to be spiritually informed in some way. Although I have neither seen nor looked for an actual survey, my experience would indicate that atheists and agnostics comprise a minority of psychotherapists.

It may be that the proportion of atheists and agnostics is higher among psychotherapists than among other helping professions, but I don't know what conclusions could be drawn from such a finding, if it is even true. One of the characteristics of a good therapist, is a willingness to ask difficult questions. Another is the ability to question things that seem obvious, just in case the obvious explanation is not the correct explanation. Atheists and agnostics tend to have those traits, perhaps a bit more commonly than religious people, but they don't have exclusive claim to those traits.

Anyway, I read a couple of the articles, and through some convoluted and probably illogical train of thought, ended up writing about Intelligent Design.

Perhaps as a result of randomness, but probably not, thx then visited here and wrote a comment. I found his comment to be helpful in my quest of trying to understand this phenomenon of intelligent people holding different opinions.

What he wrote was entirely consistent with my thesis. If a person starts out with the axiomatic belief that humans were created in God's image, then intelligent design and creationism make sense. Within the realm of pure logic, axioms are always true; anything that follows from the axiom makes sense, within that particular construct.

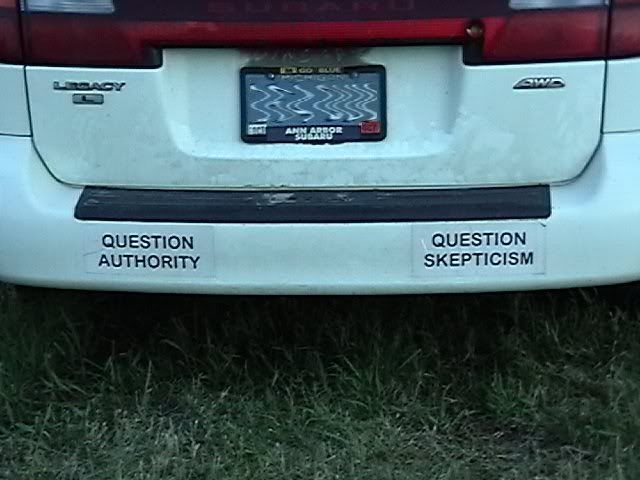

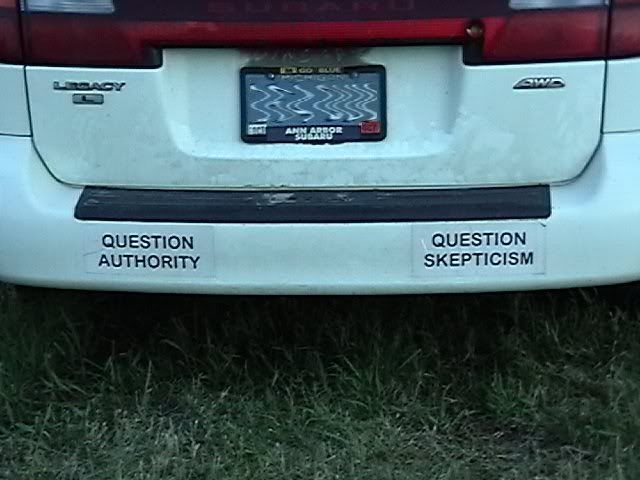

If you start with the assertion that humans were made in the image of God, it is not too big of a leap to say that there was an intelligent designer. I have absolutely no objection to that. If you want to believe that, go ahead. Put it on a t-shirt, bumper sticker, whatever. Really. If you want, I'll show you how to print bumper stickers on your inkjet printer.

I don't wash my car very often.

Does that mean that secular humanists are bad?

On the other hand, the whole flap about Intelligent Design is a different matter entirely. Intelligent Design, at least as I understand it, is based upon the assertion that mathematical and scientific principles prove that there must have been a designer.

A lot of secular commentators have said is that it is OK to teach Intelligent Design, but it should be taught in a comparative religion class. The axiom, that humans were created in the image of God, is a religious principle, not a scientific one. If that turns out to be an important concept for students of religion to know, then by all means, teach it and its corollaries. The notion, that the complexity of life proves the existence of a designer, is not supportable with current knowledge. It does not have a place in science class. This has led me to conclude that Intelligent Design is not the same as intelligent design. The former is an inappropriate attempt to introduce state-sponsored religion into schools; the latter is a perfectly reasonable construct that follows naturally from a belief that many people hold dear.

Serious comments welcome. Other comments should be made here.

(Note: The Rest of the Story/Corpus Callosum has moved. Visit the new site here.)

E-mail a link that points to this post:

Comments (1)

One of the things about humans that I think is among the most interesting, is the fact that two intelligent, sincere, well-meaning people can live in the same Universe, have access to nearly the same facts, and yet hold diametrically opposed opinions. I have known for some time that there is a certain tension between Christianity and psychotherapy, but it always has perplexed me. Most of the therapists I know are observant of some organized religion; most of those who are not, consider themselves to be spiritually informed in some way. Although I have neither seen nor looked for an actual survey, my experience would indicate that atheists and agnostics comprise a minority of psychotherapists.

It may be that the proportion of atheists and agnostics is higher among psychotherapists than among other helping professions, but I don't know what conclusions could be drawn from such a finding, if it is even true. One of the characteristics of a good therapist, is a willingness to ask difficult questions. Another is the ability to question things that seem obvious, just in case the obvious explanation is not the correct explanation. Atheists and agnostics tend to have those traits, perhaps a bit more commonly than religious people, but they don't have exclusive claim to those traits.

Anyway, I read a couple of the articles, and through some convoluted and probably illogical train of thought, ended up writing about Intelligent Design.

Perhaps as a result of randomness, but probably not, thx then visited here and wrote a comment. I found his comment to be helpful in my quest of trying to understand this phenomenon of intelligent people holding different opinions.

What he wrote was entirely consistent with my thesis. If a person starts out with the axiomatic belief that humans were created in God's image, then intelligent design and creationism make sense. Within the realm of pure logic, axioms are always true; anything that follows from the axiom makes sense, within that particular construct.

If you start with the assertion that humans were made in the image of God, it is not too big of a leap to say that there was an intelligent designer. I have absolutely no objection to that. If you want to believe that, go ahead. Put it on a t-shirt, bumper sticker, whatever. Really. If you want, I'll show you how to print bumper stickers on your inkjet printer.

I don't wash my car very often.

Does that mean that secular humanists are bad?

On the other hand, the whole flap about Intelligent Design is a different matter entirely. Intelligent Design, at least as I understand it, is based upon the assertion that mathematical and scientific principles prove that there must have been a designer.

A lot of secular commentators have said is that it is OK to teach Intelligent Design, but it should be taught in a comparative religion class. The axiom, that humans were created in the image of God, is a religious principle, not a scientific one. If that turns out to be an important concept for students of religion to know, then by all means, teach it and its corollaries. The notion, that the complexity of life proves the existence of a designer, is not supportable with current knowledge. It does not have a place in science class. This has led me to conclude that Intelligent Design is not the same as intelligent design. The former is an inappropriate attempt to introduce state-sponsored religion into schools; the latter is a perfectly reasonable construct that follows naturally from a belief that many people hold dear.

Serious comments welcome. Other comments should be made here.

(Note: The Rest of the Story/Corpus Callosum has moved. Visit the new site here.)

E-mail a link that points to this post:

Wednesday, May 11, 2005

Only Read This If You Believe in Intelligent Design

Subjective Estimates of Probability:

Earlier today, while waiting for something -- I can't even remember exactly what -- I pulled out my palm pilot (actually a Sony Clié) and started a game of yahtzee. The very first roll gave me five ones. (This really happened.)

Everyone knows that such an event is rare, but we all accept that it could happen by chance. There does not seem to be anything supernatural about it. The probability of that happening, by the way, is 1/6^5, or 1 in 7,776. Now, let's say I have a really big palm pilot, and a super-yahtzee game with one million simulated dice. I don't happen to know what 6 to the one-millionth power is, since my calculator chokes on that one. It doesn't really matter what the exact number is, though, since it is pretty obvious that it is a really big number, and the inverse is a really small number.

If I walked into Sweetwaters Cafe and ordered an expresso, then did the

same

thing with my palm pilot, and got 1,000,000 ones on the first roll,

that would be an exceptional event. In fact, if I did that

and showed it to the other customers there, most would think it had

been rigged. They would say that the probability of that

happening by chance is so low (one over six to the one millionth

power) that it could not possibly have happened by

chance. The only conclusion that would seem reasonable to

them is that it had not happened by chance.

really big number, and the inverse is a really small number.

If I walked into Sweetwaters Cafe and ordered an expresso, then did the

same

thing with my palm pilot, and got 1,000,000 ones on the first roll,

that would be an exceptional event. In fact, if I did that

and showed it to the other customers there, most would think it had

been rigged. They would say that the probability of that

happening by chance is so low (one over six to the one millionth

power) that it could not possibly have happened by

chance. The only conclusion that would seem reasonable to

them is that it had not happened by chance.

The

next day, I walk into Starbucks,

pull out my palm pilot, and get

an unremarkable mix of ones, twos, three, fours, fives, and

sixes. I shout in amazement, and show it to all the

customers. They all think I'm nuts, because there is

absolutely nothing special about that roll. Guess

what. The probability of that particular combination is

exactly the same: one over six to the one millionth power.*

That particular combination would only be interesting if I had

predicted it ahead of time.

The

next day, I walk into Starbucks,

pull out my palm pilot, and get

an unremarkable mix of ones, twos, three, fours, fives, and

sixes. I shout in amazement, and show it to all the

customers. They all think I'm nuts, because there is

absolutely nothing special about that roll. Guess

what. The probability of that particular combination is

exactly the same: one over six to the one millionth power.*

That particular combination would only be interesting if I had

predicted it ahead of time.

Now try a different thought experiment. Say that we are not going to specify ahead of time what kind of outcome we expect from the roll. We will accept any combination. What is the probability that some combination will occur? It is six to the one millionth power divided by six to the one millionth power, which is one. Once you tap the button, it is guaranteed that some outcome will occur. And the probability of any one particular outcome is exactly the same as the probability of any other outcome.

Now try the really interesting experiment. Get all six billion people on the planet to participate. Start out by rolling one dice, then two, then three, and so on. Except this time, the dice are rigged. They always will turn up with the one spot on top. After each trial, ask everyone whether that outcome could have occurred by chance. At first, everyone will agree that it could have, since it would not be unusual in a single roll of a single dice to get a one. As the number of dice thrown increases, eventually you will get some dissenters. Keep adding more dice, and the proportion of dissenters will increase. Eventually, everyone who is not up on their statistics will think it absolutely has to be rigged. They will say that there is no chance whatsoever of getting all ones that many times is a roll, with that many dice. Yet, the probability of getting all ones is no lesser and no greater that any other combination. As much as that seems contrary to intuition, as much as it seems to contradict our everyday experiences, the mathematics of it does not lie.

The Universe, of course, does not consist entirely of ones. If it did, consciousness would not be possible, and even if consciousness were possible, we'd all die of boredom. The actual Universe is made up of all kinds or numbers, some of them quite interesting. As a result, consciousness is possible, and life is interesting. The probability of this exact Universe occurring by chance is small. However, it is exactly that same as the probability of any other Universe. Therefore, it is nonsense to say that there must have been a designer in order for this Universe to have come into being.

As strange as it may seem to think that there is nothing mathematically special about the organization of the Universe we live in, the fact is, it is not special in any mathematically meaningful way. That is not to say it is not special at all: it is. However, the reason it is special is that we think it is special. We make it special.

Now try another thought experiment. Examine every brick, every molecule, every atom of the Sweetwaters Cafe at 123 W. Washington Street. Notice how carefully the bricks are arranged. Notice how the pipes go exactly to where people expect water to be available. Notice how the seats are exactly the right size for the average human to sit on. Remarkable. Now estimate the probability that another Sweetwaters will come into being at 407 N. Fifth Ave. Seems rather unlikely, doesn't it?

Earlier today, while waiting for something -- I can't even remember exactly what -- I pulled out my palm pilot (actually a Sony Clié) and started a game of yahtzee. The very first roll gave me five ones. (This really happened.)

Everyone knows that such an event is rare, but we all accept that it could happen by chance. There does not seem to be anything supernatural about it. The probability of that happening, by the way, is 1/6^5, or 1 in 7,776. Now, let's say I have a really big palm pilot, and a super-yahtzee game with one million simulated dice. I don't happen to know what 6 to the one-millionth power is, since my calculator chokes on that one. It doesn't really matter what the exact number is, though, since it is pretty obvious that it is a

really big number, and the inverse is a really small number.

If I walked into Sweetwaters Cafe and ordered an expresso, then did the

same

thing with my palm pilot, and got 1,000,000 ones on the first roll,

that would be an exceptional event. In fact, if I did that

and showed it to the other customers there, most would think it had

been rigged. They would say that the probability of that

happening by chance is so low (one over six to the one millionth

power) that it could not possibly have happened by

chance. The only conclusion that would seem reasonable to

them is that it had not happened by chance.

really big number, and the inverse is a really small number.

If I walked into Sweetwaters Cafe and ordered an expresso, then did the

same

thing with my palm pilot, and got 1,000,000 ones on the first roll,

that would be an exceptional event. In fact, if I did that

and showed it to the other customers there, most would think it had

been rigged. They would say that the probability of that

happening by chance is so low (one over six to the one millionth

power) that it could not possibly have happened by

chance. The only conclusion that would seem reasonable to

them is that it had not happened by chance.  The

next day, I walk into Starbucks,

pull out my palm pilot, and get

an unremarkable mix of ones, twos, three, fours, fives, and

sixes. I shout in amazement, and show it to all the

customers. They all think I'm nuts, because there is

absolutely nothing special about that roll. Guess

what. The probability of that particular combination is

exactly the same: one over six to the one millionth power.*

That particular combination would only be interesting if I had

predicted it ahead of time.

The

next day, I walk into Starbucks,

pull out my palm pilot, and get

an unremarkable mix of ones, twos, three, fours, fives, and

sixes. I shout in amazement, and show it to all the

customers. They all think I'm nuts, because there is

absolutely nothing special about that roll. Guess

what. The probability of that particular combination is

exactly the same: one over six to the one millionth power.*

That particular combination would only be interesting if I had

predicted it ahead of time.Now try a different thought experiment. Say that we are not going to specify ahead of time what kind of outcome we expect from the roll. We will accept any combination. What is the probability that some combination will occur? It is six to the one millionth power divided by six to the one millionth power, which is one. Once you tap the button, it is guaranteed that some outcome will occur. And the probability of any one particular outcome is exactly the same as the probability of any other outcome.

Now try the really interesting experiment. Get all six billion people on the planet to participate. Start out by rolling one dice, then two, then three, and so on. Except this time, the dice are rigged. They always will turn up with the one spot on top. After each trial, ask everyone whether that outcome could have occurred by chance. At first, everyone will agree that it could have, since it would not be unusual in a single roll of a single dice to get a one. As the number of dice thrown increases, eventually you will get some dissenters. Keep adding more dice, and the proportion of dissenters will increase. Eventually, everyone who is not up on their statistics will think it absolutely has to be rigged. They will say that there is no chance whatsoever of getting all ones that many times is a roll, with that many dice. Yet, the probability of getting all ones is no lesser and no greater that any other combination. As much as that seems contrary to intuition, as much as it seems to contradict our everyday experiences, the mathematics of it does not lie.

The Universe, of course, does not consist entirely of ones. If it did, consciousness would not be possible, and even if consciousness were possible, we'd all die of boredom. The actual Universe is made up of all kinds or numbers, some of them quite interesting. As a result, consciousness is possible, and life is interesting. The probability of this exact Universe occurring by chance is small. However, it is exactly that same as the probability of any other Universe. Therefore, it is nonsense to say that there must have been a designer in order for this Universe to have come into being.

As strange as it may seem to think that there is nothing mathematically special about the organization of the Universe we live in, the fact is, it is not special in any mathematically meaningful way. That is not to say it is not special at all: it is. However, the reason it is special is that we think it is special. We make it special.

Now try another thought experiment. Examine every brick, every molecule, every atom of the Sweetwaters Cafe at 123 W. Washington Street. Notice how carefully the bricks are arranged. Notice how the pipes go exactly to where people expect water to be available. Notice how the seats are exactly the right size for the average human to sit on. Remarkable. Now estimate the probability that another Sweetwaters will come into being at 407 N. Fifth Ave. Seems rather unlikely, doesn't it?

_________

* In real yahtzee, the position of the dice is unimportant; on the palm pilot, each simulated dice is in a fixed position. The calculation would be different if the position of each number were unimportant.

(Note: The Rest of the Story/Corpus Callosum has moved. Visit the new site here.)

E-mail a link that points to this post:

Sunday, May 08, 2005

McNamara and Bolton: a story of Fission, not Fusion

I subscribed to Foreign Policy (FP) a few months ago. Not because I have any pretensions of being a policy wonk, but because I am fascinated by what happens when you get enough molecules together in the same place. Individual molecules are fairly easy to understand, as are small collections. Most of what happens with small collections is predicable with a few simple rules.

When the number of molecules involved becomes very large -- as is the case with international politics -- the predictability vanishes. Of course, people still try to apply simple rules, then fail to notice the many exceptions. Personally, I think this is one of the most interesting aspect of human psychology. Once we establish a pet theory, we notice confirmatory evidence selectively, and take it as proof of the theory. Somehow, evidence that contradicts the theory is ignored, discounted, or otherwise invalidated.

FP is interesting to read, but it only comes out once every two months. And the US Post Office seems to take forever getting it to me. Fortunately, they have a website. Usually by the time I get the print version, I've already read most of the articles. This time, there are two in particular that I would like to mention. Both are available openly.

Apocalypse Soon

Robert McNamara is worried. He knows how close we've come to nuclear catastrophe. Forty years ago, he helped the Kennedy administration avert a nuclear war. Today, he believes the United States must no longer rely on nuclear weapons as a foreign-policy tool. To do so is immoral, illegal, and dreadfully dangerous. By Robert S. McNamara

Will the Real John Bolton Please Stand up?Yes, the first was written by that Robert McNamara, the Secretary of Defense during much of the Viet Nam war. Oddly, he is turning into a bit of a dove in his latter years. He supported an increase in our nuclear capabilities in the 1960's. Also, in an act of pure premonition, he predicted the need for the US military to increase its ability to conduct counterinsurgency (COIN) operations:

Is the man that President George W. Bush nominated to be U.N. ambassador the reform-minded, straight-talking John Bolton? Or is he the John Bolton who does not believe in the United Nations, who could not possibly build consensus in New York? Two prominent foreign policy minds—Morton Halperin and Ruth Wedgwood—face off on whether, when it comes to the United Nations, Bolton has the right stuff. By Ruth Wedgwood, Morton H. Halperin

As McNamara said in his 1962 annual report, "The military tactics are those of the sniper, the ambush, and the raid. The political tactics are terror, extortion, and assassination." In practical terms, this meant training and equipping U.S. military personnel, as well as such allies as South Vietnam, for counterinsurgency operations.We had mixed results with COIN then, as we do now. And people who think that terrorism is a new thing need to go back and learn some history. Anyway, McNamara now has taken the stage in a very prominent forum, advocating for accelerated decommissioning of our nuclear arsenal:

If the United States continues its current nuclear stance, over time, substantial proliferation of nuclear weapons will almost surely follow. Some, or all, of such nations as Egypt, Japan, Saudi Arabia, Syria, and Taiwan will very likely initiate nuclear weapons programs, increasing both the risk of use of the weapons and the diversion of weapons and fissile materials into the hands of rogue states or terrorists.This particular FP article argues only one side of the issue: the correct one. In contrast, the article about John Bolton was abstracted from a debate. Thus, it argues both sides.

By Ruth Wedgwood: [...] So this nomination is important. I’ve known John Bolton for a long time. At this time, in this place, it makes sense to put him in this job. Bolton has President George W. Bush’s confidence. When Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice travels abroad, she benefits from the fact that people know she speaks for Bush. Bolton has the same advantage and has pledged to work with Annan on reforming the United Nations. And it sometimes pays to have somebody who is hard-charging, even hard-nosed, in a job where they can put together a coalition. [...]

By Morton Halperin: [...] Why do I think that John Bolton cannot do the job Professor Wedgwood and I agree needs to be done? Not because of his temperament, but because of the views he has expressed over the course of his career. During his confirmation hearings, he had what’s called in Washington a “confirmation conversion,” in which he suddenly discovered the importance of the United Nations. But he can’t walk away from what he’s already said. [...]How are the McNamara article and the Wedgwood/Halperin article connected? John Bolton has been involved in the nuclear proliferation issue: an issue that John Kerry and George W Bush agreed (in one of their debates) is the single greatest threat to our security. And how has Bolton done with this? According to Halperin:

Yes, we have managed to renounce the ABM treaty, and Bolton negotiated a treaty with the Russians that limited strategic offensive nuclear weapons. People debate whether that treaty is useful for one second or not at all. It requires the United States to reduce its arms by some, but not very much, by the date at which the treaty expires. The next day there is no obligation at all. That’s John Bolton’s great contribution to arms control.One of the themes that runs through the article on Bolton is the notion that people can change. Wedgwood thinks that Bolton will change, if given the opportunity:

While Bolton has been in charge, North Korea has moved from possibly having two nuclear weapons to probably having 8–10, and the capacity to develop more. The United States got a deal with Libya on its WMD programs only after Bolton was taken off the case at Libya’s request. In the case of Iran, he argued for many months that we should not put any carrots on the table and simply threaten Iran after successfully invading Iraq. The administration has now repudiated that policy, and it is encouraging the Europeans to move ahead with both carrots and sticks.

Does one speak differently as a diplomat than one would on The O'Reilly Factor? Of course.Perhaps she has a valid point. McNamara has undergone a transformation; perhaps Bolton will too. Indeed, it is common for persons involved with nuclear weapons to have a change of heart. Many of the scientists who worked on the Bomb in the 1940's expressed great ambivalence. Some went so far as to campaign for limitation of the arms race. One prominent example was Philip Morrison. On the website of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, we see this:

A Spherically Curious Mind: Philip Morrison, 1915-2005

Philip Morrison, a former Bulletin contributor and one of the physicists who helped assemble the first atomic bomb, passed away on April 22. Kosta Tsipis pays tribute to the man who was a moral reference point for generations of peace advocates, opponents of nuclear weapons, and younger physicists.

Of note, the offices of the Bulletin are on the University of Chicago campus, not far from the site of the first nuclear reactor.

I

used to subscribe to the Bulletin,

long before I knew anything about, or had any interest in, the

University of Chicago. The most famous feature of the

Bulletin

is their Doomsday

Clock. In 1947, they

came up with this metaphor to describe their perception of the risk of

a nuclear war. At that time, they set the clock at seven

minutes to midnight. Keep in mind that the memory of

Hiroshima and Nagasaki was seared into everyone's mind, and the USSR

was developing nuclear weapons. In the years since, the clock

has been moved seventeen times. During the presidency of

George H. W. Bush, the clock was moved back to 11:43 PM, its farthest

excursion from midnight.

I

used to subscribe to the Bulletin,

long before I knew anything about, or had any interest in, the

University of Chicago. The most famous feature of the

Bulletin

is their Doomsday

Clock. In 1947, they

came up with this metaphor to describe their perception of the risk of

a nuclear war. At that time, they set the clock at seven

minutes to midnight. Keep in mind that the memory of

Hiroshima and Nagasaki was seared into everyone's mind, and the USSR

was developing nuclear weapons. In the years since, the clock

has been moved seventeen times. During the presidency of

George H. W. Bush, the clock was moved back to 11:43 PM, its farthest

excursion from midnight. The last movement occurred when George H. W. Bush's son was a first-term president. It now stands at 11:53 PM:

Perhaps you recall the statement of George W. Bush during his first presidential campaign, when he stated he would be "a uniter, not a divider." Now, the political landscape is more fractured than any time within my memory, the Doomsday Clock has been moved closer to midnight, and Mr. Bush wants to send one of the most divisive characters in Washington to represent us to the United Nations. The icing on the cake: he wants to fund research on a new generation of nuclear weapons (462KB PDF).

When George W. Bush spoke of uniting and dividing, we thought he was talking about the choices that politicians make: whether to promote compromise, or unilateralism. No, he was talking about whether he would promote nuclear fission weapons, or fusion. Now we know the truth: it's nuclear fission. He's a divider after all.

(Note: The Rest of the Story/Corpus Callosum has moved. Visit the new site here.)

E-mail a link that points to this post: