Friday, July 02, 2004

PTSD Among American Service Personnel

ABSTRACT

Background: The current combat operations in Iraq and Afghanistan have involved U.S. military personnel in major ground combat and hazardous security duty. Studies are needed to systematically assess the mental health of members of the armed services who have participated in these operations and to inform policy with regard to the optimal delivery of mental health care to returning veterans.

Methods: We studied members of four U.S. combat infantry units (three Army units and one Marine Corps unit) using an anonymous survey that was administered to the subjects either before their deployment to Iraq (n=2530) or three to four months after their return from combat duty in Iraq or Afghanistan (n=3671). The outcomes included major depression, generalized anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), which were evaluated on the basis of standardized, self-administered screening instruments.

Results: Exposure to combat was significantly greater among those who were deployed to Iraq than among those deployed to Afghanistan. The percentage of study subjects whose responses met the screening criteria for major depression, generalized anxiety, or PTSD was significantly higher after duty in Iraq (15.6 to 17.1 percent) than after duty in Afghanistan (11.2 percent) or before deployment to Iraq (9.3 percent); the largest difference was in the rate of PTSD. Of those whose responses were positive for a mental disorder, only 23 to 40 percent sought mental health care. Those whose responses were positive for a mental disorder were twice as likely as those whose responses were negative to report concern about possible stigmatization and other barriers to seeking mental health care.

Conclusions: This study provides an initial look at the mental health of members of the Army and the Marine Corps who were involved in combat operations in Iraq and Afghanistan. Our findings indicate that among the study groups there was a significant risk of mental health problems and that the subjects reported important barriers to receiving mental health services, particularly the perception of stigma among those most in need of such care.

|

The data presented by Hoge and associates in this issue of the Journal1 about members of the Army and the Marine Corps returning from Operation Iraqi Freedom or Operation Enduring Freedom in Afghanistan force us to acknowledge the psychiatric cost of sending young men and women to war. It is possible that these early findings underestimate the eventual magnitude of this clinical problem. The report is unprecedented in several respects. First, this is the first time there has been such an early assessment of the prevalence of war-related psychiatric disorders, reported while the fighting continues. Second, there are predeployment data, albeit cross-sectional, against which to evaluate the psychiatric problems that develop after deployment. Third, the authors report important data showing that the perception of stigmatization has the power to deter active-duty personnel from seeking mental health care even when they recognize the severity of their psychiatric problems. These findings raise a number of questions for policy and practice. I focus here on post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), because there is better information about this disorder than about others and because PTSD was the biggest problem noted in the responses to an anonymous survey among those returning from active duty in Iraq or Afghanistan. [...]

Collaboration between mental health professionals in the Department of Defense and those in the Department of Veterans Affairs is at an all-time high. For example, the Veterans Affairs National Center for PTSD and the Defense Department's Walter Reed Army Medical Center collaborated to develop the Iraq War Clinician Guide (available at www.ncptsd.org/topics/war.html) and to conduct a multisite, randomized trial of cognitive–behavioral therapy for PTSD among female veterans and female active-duty personnel. [...]

Hoge and associates suggest that the perception of stigmatization can be reduced only by means of concerted outreach — that is, by providing more mental health services in primary care clinics and confidential counseling through employee-assistance programs. The sticking point is skepticism among military personnel that the use of mental health services can remain confidential. Although the soldiers and Marines in the study by Hoge and colleagues were able to acknowledge PTSD-related problems in an anonymous survey, they apparently were afraid to seek assistance for fear that a scarlet P could doom their careers.

Our acknowledgment of the psychiatric costs of war has promoted the establishment of better methods of detecting and treating war-related psychiatric disorders. It is now time to take the next step and provide effective treatment to distressed men and women, along with credible safeguards of confidentiality.

Of particular interest here is the link to the Iraq War Clinician Guide. Despite the name, there is a lot of information there that is non-technical and suitable for patients and families. One of the great tragedies of the Vietnam War was the lack of acceptance and understanding of veterans with PTSD. It is extremely important that we not repeat that mistake. Therefore, I urge everyone to become acquainted with the information at www.ncptsd.org/topics/war.html. For example:

Personal Emergency Preparedness Brochure from the Department of Veterans Affairs

Preparedness Brochure (download)

The Family Deployment Guide by Department of the Army, Headquarters, 88th Regional Support Command, 506 Roeder Circle, Fort Snelling, MN 55111-4009

Preparing for

Deployment

Leaving Your Loved Ones

Behind

Children and Deployment

Communication

Finances

Resources

Military Benefits

Glossary

For a good quick reference to the clinical aspects of PTSD, see this

link. The clinical diagnosis of PTSD has been

controversial. Although the controversy is resolving slowly, it

certainly has not gone away. For some insight into the history of

the controversy, see this

link, to an article by Rachel Yehuda. Dr. Yehuda points out

that the original concept of PTSD was that it was essentially a normal

response to extreme stress. She points out, though, that the

concept had to be revised when a distinct set of neurobiological

changes was documented in various research studies. A

counterpoint is presented by Derek Summerfield, here.

Dr. Summerfield's article is entitled: The invention of post-traumatic stress

disorder and the social usefulness of a psychiatric category.

Personally, I think Dr. Summerfield has it all wrong. The

publisher of his article, the British Medical Journal, also has online

a bunch

of letters written in response to Dr. Summerfield's

article. A particularly amusing one was written by Dr. Arieh Y

Shalev, who is a psychiatrist in Jerusalem, who undoubtedly has vast

experience treating PTSD patients.

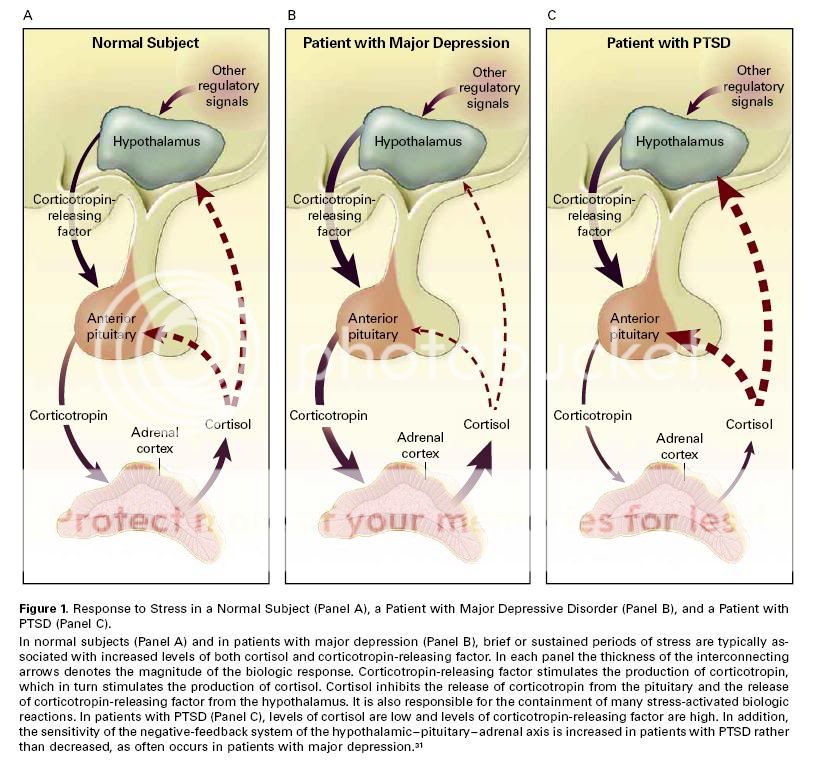

The neurobiology of PTSD is, at this point, very well

documented. It really is beyond controversy to say that there

really is something wrong, biologically, in patients with PTSD. I

can't legally post the entire text of Dr. Yehuda's summary article on

the neurobiology of PTSD, but I did upload an illustration:

(Click to enlarge)

(from: N Engl J Med, Vol. 346, No. 2 - January 10, 2002)

It simply is not reasonable to attribute this to a "social

construct." The abnormalities of the HPA axis are profound, the

observations have been replicated by numerous researchers, and the

specificity of the finding to PTSD patients is striking. There

are many other examples of neurobiological abnormalities in PTSD.

See this

article from Discover magazine for more information, of a

less technical sort.

In summary, we see that there is evidence that there is a

significant risk for PTSD among American service personnel in Iraq,

that the military is taking steps to address this, that some persons

feel that the military is not doing enough, and that -- despite

the earlier controversy -- there is substantial, compelling evidence

for a distinct set of abnormal neurobiological processes in patients

with PTSD. Although some may continue to argue that PTSD is not a

real disease, that position is becoming increasingly untenable.

In order to avoid a repetition of the secondary trauma that was

experienced by so many Vietnam vets, it would be good for the entire

public in the USA to become more familiar with these issues.

(Note: The Rest of the Story/Corpus Callosum has moved. Visit the new site here.)

E-mail a link that points to this post: